So the Independent Evaluation Office of the IMF has issued a mea culpa on the handling of the euro crisis. The sub-report on Greece in particular admits to very serious errors in handling the crisis, although it falls short of claiming at least partial ownership of the social and humanitarian disaster inflicted on the mass of the population in Greece. Apparently, and tellingly, it considers its programs in Spain, Portugal and Ireland as various shades of quasi-successful, as far as the IMF goals are concerned, which is probably true, but says more about the nature of IMF goals and what they do not include, given the various levels of social dislocation, hardship, increased suicide rates, increased inequality and migration rates in these austerityland countries. It focuses (rightly) on the lack of serious debt restructuring efforts early on in the crisis (due as we know, and the reports admit, to EU-level political reaction to any such plan), admits to a lack of understanding of the intricacies of the Greek economy (such that it was) and on pre-crisis assessments of it, and recognizes that the "burden-sharing" of the adjustment in Greece was very lopsided. Also and importantly it points out that:

Interestingly the report focuses on the issue of a more just burden-sharing mostly because the authors apparently imagine that if this "adjustment" was more fair - in terms of taxing the rich a bit more - then the population would have fallen behind and accepted the IMF programme. But although such a redistribution of tax burden and legal proceedings against tax-evaders would admittedly create less rage against the program, it would have marginal at best success in increasing revenues. As the current government, after the July 2015 coup in which the IMF participated, is now focusing on exactly this redistribution and does go after (many) tax-evaders (certainly to a degree not seen in Greece since practically forever), tax arrears keep piling up because what is (or was) the middle class has been taxed out of its safety nets already, property taxes are at an unbelievably high rate (and since something like 80% of Greeks own their homes this affects even people who are truly struggling), small businesses have collapsed and those that survive are mostly fighting for their lives. and troika imposed VAT hikes are hitting everyone and affecting the tourist industry. You cannot receive from those who have nothing left to give. For probably most households and small businesses piling up arrears and tax-evading is a question of economic survival and sustaining a very modest living standard. No amount of fairness can erase this simple fact, which somehow escaped the grasp of the IMF as it still assumes that the increase in arrears is a question of reluctance not inability.

As these reports are published, the IMF is still involved in Greece and is pushing hard for further labor market deregulation, further reductions in the minimum wage and even laxer mass layoff laws. The current Greek government is insisting that not only will it not accept these terms, but will push for restoration of some form of collective bargaining. So this is heading for a multiple stand-off this coming autumn, pitting the IMF against the rest of the lenders on debt reduction and the IMF against the Greek government in terms of labor reforms. It is questionable whether these recent reports will have any effect on IMF policy within the troika, especially since the IMF research teams and various committees have continuously offered critiques of IMF policy in Greece and were practically ignored by its executive.

Still, things are in motion, especially after BRexit and the Spain and Portugal amnesty decisions on their "excessive deficit" that were driven by it, as well as the looming Italian (european?) banking crash / rule bending. This report adds to the argument that turning a blind eye on debt sustainability is a can that can be kicked along no further, a position already gaining ground inside the organization itself and supported apparently by the US government.

As a refresher on the IMF's blunders and misinformation in Greece I am republishing below a diary I posted in the European Tribune in May 25, 2010, titled "Some somewhat more coherent notes on the Greek crisis: debunking IMF propaganda (2)" with updated links, minor edits and restored graphs (part 1 was here), based on an IMF FAQ on the Greek crisis, and its Frequently Wrong Answers:

If preventing international contagion was an essential concern, the cost of its prevention should have been borne – at least in part – by the international community as the prime beneficiaryAt the same time it ignores the social catastrophe that was produced by its "structural adjustment" pre-conditions in:

- labor deregulation (in an economy with inter alia disaster-area unemployment rates, a war-time level of GDP reduction, and a massive brain-drain as educated young people left and are still leaving the country to escape a prospect of life-long poverty wages),

- privatizations (which they admit had highly inflated revenue goals, but have no problem with the fire-sale of state assets that they contributed in imposing)

- the "opening of professions" (which is leading either to a proletarianision of professionals - contributing to the aforementioned brain-drain and the creation of ever-tightening, usually foreign-owned oligopolies),

- or most of the rest of the other half-baked neoliberal snake oil they peddle (such as the "liberalization" of market opening hours).

Interestingly the report focuses on the issue of a more just burden-sharing mostly because the authors apparently imagine that if this "adjustment" was more fair - in terms of taxing the rich a bit more - then the population would have fallen behind and accepted the IMF programme. But although such a redistribution of tax burden and legal proceedings against tax-evaders would admittedly create less rage against the program, it would have marginal at best success in increasing revenues. As the current government, after the July 2015 coup in which the IMF participated, is now focusing on exactly this redistribution and does go after (many) tax-evaders (certainly to a degree not seen in Greece since practically forever), tax arrears keep piling up because what is (or was) the middle class has been taxed out of its safety nets already, property taxes are at an unbelievably high rate (and since something like 80% of Greeks own their homes this affects even people who are truly struggling), small businesses have collapsed and those that survive are mostly fighting for their lives. and troika imposed VAT hikes are hitting everyone and affecting the tourist industry. You cannot receive from those who have nothing left to give. For probably most households and small businesses piling up arrears and tax-evading is a question of economic survival and sustaining a very modest living standard. No amount of fairness can erase this simple fact, which somehow escaped the grasp of the IMF as it still assumes that the increase in arrears is a question of reluctance not inability.

As these reports are published, the IMF is still involved in Greece and is pushing hard for further labor market deregulation, further reductions in the minimum wage and even laxer mass layoff laws. The current Greek government is insisting that not only will it not accept these terms, but will push for restoration of some form of collective bargaining. So this is heading for a multiple stand-off this coming autumn, pitting the IMF against the rest of the lenders on debt reduction and the IMF against the Greek government in terms of labor reforms. It is questionable whether these recent reports will have any effect on IMF policy within the troika, especially since the IMF research teams and various committees have continuously offered critiques of IMF policy in Greece and were practically ignored by its executive.

Still, things are in motion, especially after BRexit and the Spain and Portugal amnesty decisions on their "excessive deficit" that were driven by it, as well as the looming Italian (european?) banking crash / rule bending. This report adds to the argument that turning a blind eye on debt sustainability is a can that can be kicked along no further, a position already gaining ground inside the organization itself and supported apparently by the US government.

As a refresher on the IMF's blunders and misinformation in Greece I am republishing below a diary I posted in the European Tribune in May 25, 2010, titled "Some somewhat more coherent notes on the Greek crisis: debunking IMF propaganda (2)" with updated links, minor edits and restored graphs (part 1 was here), based on an IMF FAQ on the Greek crisis, and its Frequently Wrong Answers:

Some somewhat more coherent notes on the Greek crisis: debunking IMF propaganda (2010, edited and restored, 2016)

I was thinking about how to structure the second installment of the saga of this unfolding disaster (part 1 here) that has been inflicted on the Greek working population, part of the development of the Great Crash of 08. There is a lot to be highlighted, especially bogus data and statistics circulating among world media and organizations, that are then used to "explain" the inevitability of the neoliberal shock therapy which Greece is being subjected to (and which is I am afraid a first test for far wider application of similar shocks throughout the continent ).The IMF fortunately, I see, has helped me out a bit on this, by issuing a compilation of bad statistical urban legends and hearsay on the Greek crisis and endorsing it as policy background. In its web-site, the Fund has thus created an FAQ section on the Greek crisis. This is a document riddled with outright lies and strategically propagated half-truths and obfuscations, along with wishful thinking and hand-waving serious questions aside, to an extent impressive for an official document, coming from one of the pillars of the world economy. It is the ideal place to start to tackle the (already dwindling in the face of the globalisation of the Euro crisis) moralizing and the lies that have been used to "explain" why working Greeks should suffer the economic equivalent of a nuclear attack. Let's check out some of the claims made to see how credible the IMF's analysis of the statistical and factual reality in Greece is...

1. Right off the bat the IMF starts with a much-repeated, yet misleading, claim:"Greece is highly indebted and lost about 25 percent of its competitiveness since Euro adoption".It is far from obvious how the IMF measures competitiveness. The FAQ section is not referenced at all, and it's not clear how this quantification arises or what it means. Erik Jones, writing in Euro Intelligence, was already debunking part of the competitiveness mythology, as pertains to labor costs, in March:...What matters in terms of a head-to-head competition is how Greece and Germany compare in the cost of labor per unit of output and not the real compensation of employees. Moreover, we should look at their performance across the European marketplace as a whole. By that measure, if we set the year 2000 equal to 100, then by 2009 Greece was at 98 while Germany was at 95. Germany is still doing better than Greece, but only by a little and both have improved against the rest of Europe.

...Using national accounts data for relative real unit labor costs in manufacturing, Greece goes from 100 in the year 2000 to 87 in 2008. Over the same period, Germany goes from 100 to 90. It is hard to see how Germany comes off better in the comparison.

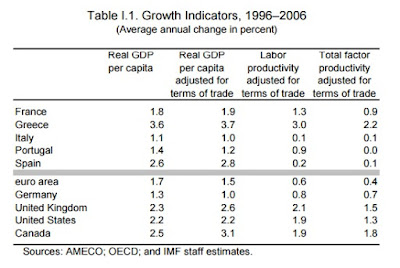

...Even if Greece is not suffering in terms of manufacturing, the high real incomes that Greek employers are doling out must surely be hitting the bottom line in the service sector, shouldn't they? Again, that's hard to see in the data. Total compensation per employee was 53.8 percent in Greece and 57 per cent in Germany...Furthermore the "since Euro adoption" part is misleading. Greek productivity was surging until 2007. After that year, influenced of course by the global crisis, and affected by real fiscal imbalances (about which more later) productivity (and competitiveness, however defined) fell faster than the Dow Jones average after a computer glitch, but that was surely not a uniquely Greek phenomenon.In fact Greece was receiving praise by the IMF itself for its improved competitiveness, singled out as the most successful economy in Southern Europe.Source: IMFSo, much of the decline, in many areas, was a result of Greece not responding successfully to the global crisis. The "joining the Euro" part is thus, I repeat, misleading. And the whole story is repeated elsewhere in the document.

2. Under the same question the IMF then makes a flatly false statement:In past years, Greece's public sector spending grew, while revenue fell. Then the global recession hit and economic activity slowed and unemployment rose. This exacerbated the fiscal situation.Well no. The evolution of Greek public sector spending was not growth followed by a dip as the Greek economy was hit by the global recession. In fact between 2002 and 2006 public expenditure shrank and started rising precipitously, only after the global recession hit... but then so it did almost everywhere...

Greece / OECD public revenues as % of GDP. Source: OECD

Greece / Eurozone public expenditure as % of GDP. Source: TradingEconomics.com

Revenue was pretty much stable at rather low levels until just last year (2009) when indeed, it did drop.3. Fluffy nonsense:A significant fiscal adjustment is needed in Greece. The program is designed so that the burden of adjustment is shared across all levels of society, while protecting the most vulnerable groups.Bollocks. According to most reports in the Greek press, the lower pensions are being lowered still and will then remain steady (or decline) at below poverty levels for the next few years. The minimum wage is effectively being driven down. So are disability pensions. At the same time while tax-evasion is being targeted, employers are receiving new-found "freedom" from labor costs.The government's program also includes pro-growth policies to reform such crucial sectors as tax administration, the labor market, the health sector, and the management of public finances.

None of these is strictly speaking a pro-growth policy. They are trying to clean up parts of the tax collecting system (although with limited resources, a diminishing budget - due to the cuts - no possibility of hiring tax inspectors and public service auditors etc.). The labor market is the one area they have been "pro-growth": its being third-worldized.

These measures will open up the economy to opportunity and make the economy more competitive, transparent, and efficient. This in turn will help restore confidence of investors and the markets. The ultimate goal is more dynamic and durable growth.... many years from now, by which time the basic salary will be around 100 Euros or so. Hurray! Although it is probably true that investors and markets, will really like the new Greece.

4. And we thus move on to yet another falsehood:The fiscal measures include: a reduction of public sector wages and pensions--something which is unavoidable given that these two elements alone constitute some 75 percent of total (non-interest) public spending in Greece.The 75% figure is completely false AFAICS and we've seen why here: These are the Eurostat numbers (p. 15), and this is the Greek Ministry's of Finance planned 2010 budget [in Greek, see p.11, budgetary expenditure]. At most these add up to 45% of total (non-interest) public spending in Greece. So maybe this wasn't really "unavoidable".

5. The response to the "but isn't this the bad ol' IMF doing its destructive work again":Q. Is the range of conditionality in the Greek program a return to the more traditional IMF "austerity" measures of the past?

No. There are three key differences:

- This program is focused on Greece' two key problems: high debt and a lack of competitiveness. Conditionality is very much focused on these issues.

- The Greek authorities have strong ownership and leadership and it is their program.

- The program includes measures to protect the most vulnerable, which are a critical component to effective implementation.

Well:

- The Greek authorities claim that they have no such ownership and that they cannot draw "lines in the sand", except with great difficulty, where the measures are concerned. In fact according to the media, the Greek government is under enormous pressure from the IMF/EU Commission to further transform the pensions' system. One party is lying.

- I have not noticed any of these "protective" measures being reported. What, they'll bring in UNICEF when child mortality rises?

6. The IMF insists that debt restructuring is not in Greece's interest, and that it will not help "Greece's capacity to grow". I wonder how mass migration of the young and talented will help "Greece's capacity to grow", a trend that existed already but now seems on the verge of reaching tragic proportions, or how is the deepest recession since Nazi occupation, conductive to "Greece's capacity to grow", unless they mean reaching such depths of poverty that Greece can compete with Vietnam in real wages, and Foxconn finds it profitable to move its factories and labor practices from mainland China to Greece. How will deep cuts in education help "Greece's capacity to grow"? How will an organized restructuring not help Greece's capacity to grow, if the alternative is an economic collapse and a recovery prospect based on wishful thinking and a best case scenario regarding world growth? How deep will the recession have to be this year (let alone the next and the one after that) before the IMF "revises" its outlook? Because we certainly are not heading toward a 4% of GDP recession: "market sources", are already whispering double digits.

7. Regarding tax revenues the IMF states that:Additional specified tax measures amount to about 4 percent of GDP. The government is proposing measures to overhaul the tax system, including a progressive tax scale for all sources of income, taxing luxury goods, higher taxes for the wealthy, and higher taxes on tobacco and alcohol.That's all fine and well, but we're already seeing the failure of this policy to raise indirect taxes. Consumption has already dropped so much that the new taxes on cigarettes are not expected to raise revenues at all, while enriching cigarette smugglers. The five point increase in the VAT tax will mean less revenue for the government if, as it seems certain, consumption drops by more than 8% this year. Anyway it seems ironic that the IMF under its explanation for the increase in VAT mentions that "The government has proposed a range of tax measures with the aim of spreading the burden of adjustment more fairly". Obviously huge increases in indirect taxation, do not help in tax fairness, eh?

8. The IMF explains that the wage and pension cuts the government is proposing...will bring Greece in line with other, more competitive, economies. The extra two months salaries--the so-called "13th and 14th" payments--are unsustainable and do not exist in many other countries. Nor is the low retirement age that begins around 50 for some groups in line with life expectancy.This is highly misleading to the point of dishonesty:This in a country where 28% of the over 65-year-olds are living under the official poverty line...

- The 13th and 14th payments are just a particular way to temporarily distribute annual income. The only measure of wages that is meaningful is on a yearly basis. According to the European Economy Statistical Annex of 2007, Greece was second from the bottom in average wage purchasing power in the EU-15.

- Some people do retire early, as early as 41. These are few. Very few. Mostly in the Armed Forces (where they can retire and then get another job legally, meaning they continue contributing to the system) and the police. Also until recently women working in the public sector with underage children qualified for early retirement at 50+. But the average retirement age in the economy as a whole is 61 years. These reforms pretty much push full retirement for many people at around 67. Mentioning that some retire as early as 50 and stopping at that, is monstrously misleading. This piece of misinformation has been repeated ad nauseam around the global media (i.e.). And it is actually repeated again in the document:

The pensionable retirement age for some groups beginning at around 50 is out of line with life expectancy in Greece--and out of line with the rest of the Euro zone countries. Given the aging of the population, such a low age for pensions, coupled with generous coverage ratios to last earned income, has put far too much strain on Greece's public finances.

9. The IMF claims that:The authorities recognize that the public sector in Greece has become too large and costly for the economy. In fact, there is no clear data on exactly how many people are working in the public sectorThis is again not really true. The public sector amounts to 40% of GDP, according to the CIA factbook (I couldn't find directly comparable numbers for the rest of the EU), while "The share of public sector GDP in total GDP is about 43 percent in the UK and about 54 percent in France".The data on how many people work in the Public sector exactly might not be all in, but we do have a rather good ballpark estimate. It is 14% of the workforce, "very close to the OECD average" as the OECD itself notes. The OECD is not including non-permanent seasonal and temporary employees which are between 300.000-500.000 in a given year (mostly underpaid and underinsured), and together both categories add up to something close to 20% of workforce (which is around 5 million). This is hardly a bloated public sector. It is inefficient, corrupt and poorly organized, yet surely its reduction (which is also a Greek government/IMF project), as opposed to its reinvention, reorganization, repair etc will only have the effect of ruining the few crumbs of a social safety net that do exist. That both the IMF and the Papandreou government see this as something desirable, speaks volumes about their ideology.

10. Handwaving on the most crucial question, is not a good sign that the Fund is seriously concerned about the future of the Greek economy or Greeks in general:Q. With lower revenue and a stagnating economy, how will Greece begin to grow again?The government's program recognizes, and takes into consideration, that the difficult fiscal adjustment will initially have a negative effect on growth.

But with effective implementation of the fiscal and structural policies and the support of the Greek people, the economy will be far better placed to generate higher growth and employment than in the past.Meaning: We know the effect on growth will be somewhere from horrible to catastrophic, yet if we all get together and engage in wishful thinking we will do what has never been done before and get Greece to the neolib fantasy of prosperity, with third world wages and most of its trained youth living somewhere far away. This is based on pretty much the sort of magical thinking that has made the IMF synonymous with disaster. So if our best case scenario regarding the world economy holds up, and if Greece is very, very lucky, it might return to 2009 levels of GDP by 2025 or so. Impressive.

11. As final proof that the people who wrote the FAQ are kidding, you have their take on unemployment:Because of the crisis, employment is already high at about 10-11 percent. Initially, there will be an increase in unemployment and the next two years will be difficult - unemployment could rise to about 15 percent. However, as strong medium-term fiscal measures and productivity-boosting reforms kick in, the economy will become more competitive, transparent, and efficient. With confidence returning, Greece will emerge from this experience in better shape than before, growth will return and employment will pick-up.This 15 percent is utter fiction. The labor minister even before the IMF/Commission demolition combo landed in Athens was projecting unemployment rates around 17% by the end of the year. 15% is laughably low. Already in May unemployment had reached 12,1 percent up from 9,1 last May, and on a steep slope towards the stars. And this is pretty much before the austerity measures kicked in. I'm willing to bet that we will be lucky to have 15% unemployment by the end of this year. Next year we will most probably reach 20% or more. Among young people 18-24 unemployment is already at a staggering 34% this month.

12. Final question:Q. Has any country undertaken this level of fiscal adjustment before?It is an unprecedented adjustment, but it is feasible, and the government is committed to getting the job done.Feasible if one believes this absolutely speculative and factually false account given by the IMF. But anyway, this is an admission that Greece is the first guinea pig, an experiment to see if any First World country can survive the IMF treatment without joining the Third World.Greece in particular will end up having transitioned from a hell of an inefficient and corrupt social model to no social model at all...Finally:The fact that the IMF has been so clumsy in its description of the Greek situation (and so unrealistic on the effects the policies it is imposing will have, or are having), either reveals the quality of the analysis of the Greek economy that has driven the IMF's/EU advice - a bad sign surely, or demonstrates that the IMF is barely covering up for decisions of which it is only an implementation instrument. Alternatively they don't care enough to be serious...